The job market for API technical writers

Demand is high

Technical writers who can write developer documentation are in high demand, especially in the Silicon Valley area. There are plenty of technical writers who can write documentation for graphical user interfaces but not many who can navigate the developer landscape to provide highly technical documentation for developers working in code.

In this section of my API documentation course, I'll dive into the job market for API documentation.

Ability to read programming languages

In nearly every job description for technical writers in developer documentation, you'll see requirements like this:

Ability to read code in one or more programming languages, such as Java, C++, or Python.

You may wonder what the motivation is behind these requirements, especially if the core APIs are RESTful. Here's the most common scenario. The company has a REST API for interacting with their services. However, to make it easy for developers, the company provides SDKs and client implementations in various languages for the REST API.

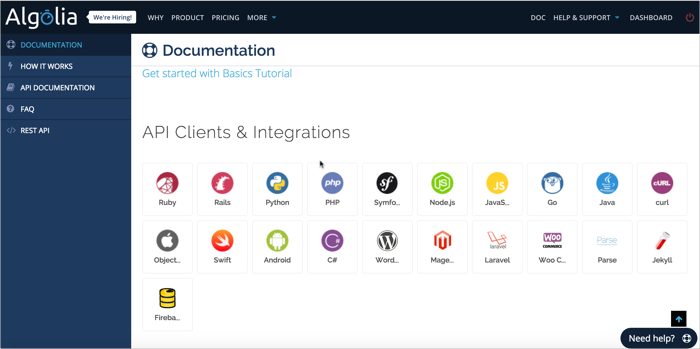

Take a look at Algolia's API for an example. You can view the documentation for their REST API here. However, when you implement Algolia (which provides a search feature for your site), you'll want to follow the documentation for your specific platform.

Although users could construct their own code when using the REST endpoints, most developers would rather leverage existing code to just copy and paste what they need.

When I worked at Badgeville, we developed a collection of JavaScript widgets that provided code developers could easily copy and paste into their web pages, making a few adjustments as needed. Sure developers could have created their own JavaScript widget code based on calls to the REST endpoints, but sometimes it can be tricky to know how to retrieve all the right information and then manipulate it in the right way in your language.

Remember that developers are typically using a REST API as a third-party service. The developer's main focus is his or her own company's code; they're just leveraging your REST API as an additional, extra service. As such, the developer wants to just get in, get the code, and get out. This is why companies need to provide multiple client references in as many languages as possible — these client implementations make it easy for developers to implement the API.

If you were recruiting for a technical writer to document Algolia, how would you word the job requirements? Can you now see why even though the core work involves documenting the REST API, it would also be good to have an "ability to read code in one or more programming languages, such as Java, C++, or Python."

Technical writers who are former programmers

When faced with these multi-language documentation challenges, hiring managers often search for technical writers who are former programmers to do the tasks. There are a good number of technical writers who were once programmers, and they can command more respect and competition for these developer documentation jobs.

But even developers will not know more than a few languages. Finding a technical writer who commands a high degree of English language fluency in addition to possessing a deep technical knowledge of Java, Python, C++, .NET, Ruby, and more is like finding a unicorn. (In other words, these technical writers don't really exist.)

If you find one of these technical writers, the person is likely making a small fortune in contracting rates and has a near limitless choice of jobs. Companies often list knowledge of multiple programming languages as a requirement, but they realize they'll never find a candidate who is both a Shakespeare and a Steve Wozniak.

Why does this hybrid individual not exist? In part, it's because the more a person enters into the worldview of computer programming, the more they begin thinking in computer terms and processes. Computers by definition are non-human. The more you develop code, the more your brain's language starts thinking and expressing itself with these non-human, computer-driven gears. Ultimately, you begin communicating less and less to humans using regular speech and fall more into the non-human, mechanical lingo.

This is both good and bad — good because other engineers in the same mindset may better understand you, but bad because anyone who doesn't inhabit that perspective and embrace the terminology already will be somewhat lost.

Remember that the terminology and model will vary from one language and platform to the next. One user may speak fluently in Ruby, but that language may not connect with somebody who is a .NET developer. Consequently speaking "geek" can both connect with some developers and backfire with other developers.

Wide, not deep understanding of programming

Although you may have client implementations in a variety of programming languages, the implementations will be brief. The core documentation needed will most likely be for the REST API, and then you will have a variety of reference implementations or demo apps in these other languages.

You don't need to have deep technical knowledge of each of the platforms to document them. You're probably just scratching the surface with each of them.

As such, your knowledge of programming languages has to be more wide than deep. It will probably be helpful to have a grounding in fundamental programming concepts, and a familiarity across a smattering of languages instead of in-depth technical knowledge of just one language.

Having broad technical knowledge of 6 programming languages isn't really easy to pull off, though. As soon as you throw yourself into learning one language, the concepts will likely start blending together.

And unless you're immersed in the language on a regular basis, the details may never fully sink in. You'll be like Sisyphus, forever rolling a boulder up a hill (learning a programming language), only to have the boulder roll back down (forgetting what you learned) the following month.

Undoubtedly, technical writers are at a disadvantage when it comes to learning programming. Full immersion is the only way to become fluent in a language, whether referring to programming languages or spoken languages like Spanish. I studied Spanish for 3 years in high school, but it wasn't until I lived in Venezuela and interacted with locals for 6 months continuously speaking Spanish that the language finally clicked for me.

As such, you might consider diving deep into one core programming language (like Java) and briefly playing around in other languages (like Python, C++, .NET, Ruby, Objective C, and JavaScript).

Of course, you'll need to find a lot of time for this as well. Don't expect to have much time on the job for actually learning it. It's best if you can make learning programming one of your "hobbies."

Diverse technical landscape

The technical landscape is diverse, so the generalizations I'm providing here may not hold true in all companies. You may be in a Java or JavaScript shop where all you need to know is Java/JavaScript. If that's the case, you'll need to develop a deeper knowledge of the programming language so you can provide more depth.

However, with the proliferation of REST APIs, this scenario is much less common. Companies can't afford to cater only to one programming language. Doing so drastically reduces their audience and limits their revenue. The advantages of providing a universally accessible API using any language platform usually outweigh the specifics you get from a native library API.

The company I currently work for has a Java, .NET, and C++ API that each do the same thing but in different languages. Maintaining the same functionality across three separate platforms is a serious challenge for developers. Not only is it difficult to find skill sets for developers across these three platforms, having multiple code bases makes it harder to test and maintain the code. It's three times the amount of work, not to mention three times the amount of documentation.

Additionally, since native library APIs are implemented locally in the developer's code, it's almost impossible to get users to upgrade to the latest version of your API. You have to send out new library files and explain how to upgrade versions, licenses, and other deployment code.

If you've ever tried to get a big company with a lengthy deployment process on board with making updates every couple of months to the code they've deployed, you realize how impractical it is. Rolling out a simple update can take 6 months or more.

It's much more feasible for API development shops to move to a SaaS model using REST, and then create various client implementations that briefly demonstrate how to call the REST API using the different languages. With a REST API, you can update it at any time (hopefully maintaining backwards compatibility), and developers can simply continue using their same deployment code.

The more you can facilitate implementation in the user's desired language, the higher your chances of implementation — which means greater product adoption, revenue, and success.

Consolations for technical writers

This proliferation of code and platforms creates more pressure on the multi-lingual capabilities of technical writers. Here's one consolation, though. If you can understand what's going on in one programming language, then your description of the reference implementations in other programming languages will follow highly similar patterns.

What mainly changes across languages are the code snippets and some of the terms. You may refer to "functions" instead of "classes," and so on. Even so, getting all the language right can be a serious challenge, which is why it's so hard to find technical writers who have skills for producing developer documentation.

With this scenario of having multiple client implementations, you'll face other challenges, such as maintaining consistency across the various platforms. As you try to single source your explanations for various languages, your documentation code will become complex and difficult to maintain.

Additionally, product managers may want you to push out separate outputs within each programming language channel to keep things simple for the users. Can you imagine pushing out a dozen different outputs across different languages for content that follows highly similar patterns and has common explanations but differs in just enough ways to make single sourcing from the same core content an act of sorcery? Here is where you have to put your technical writing wizard hat on and pull off level 9 incantations.

Not an easy problem to solve

The diversity and complexity of programming languages is not an easy problem to solve. To be a successful API technical writer, you'll likely need to incorporate at least a regular regiment of programming study.

Fortunately, there are many helpful resources (my favorite being Safari Books Online). If you can work in a couple of hours a day, you'll be surprised at the progress you can make.

Some of the principles that are fundamental to programming, like variables, loops, and try-catch statements, will begin to feel second-nature, since these techniques are common across almost all programming languages. You'll also be equipped with a confidence that you can learn what you need to learn on your own (this is the hallmark of a good education).

But in discussions with hiring managers looking to fill 6-month contracts for technical writers already familiar with their programming environment, it will be a hard sell to persuade the manager that "you can learn anything."

The truth is that you can learn anything, but it may take a long time to do so. It can take years to learn Java programming, and you'll never get the kind of project experience that would give you the understanding that a developer possesses.

Strategies to get by

When you work in developer documentation environments, one strategy is to interview engineers about what's going on in the code, and then try your best to describe the actions in as clear speech as possible.

You can always fall back on the idea that for those users who need Python, the Python code should look somewhat familiar to them. Well-written code should be, in some sense, self-descriptive in what it's doing. Unless there's something odd or non-standard in the approach, engineers fluent in code should be able to get a sense of what the code is doing.

In your documentation, you'll need to focus on the higher level information, the "why" behind the approach, the highlighting of any non-standard techniques, and the general strategy behind the code.

Just remember that even though someone is a developer, it doesn't mean he or she is an expert with all code. For example, the developer may be a Java programmer who knows just enough iOS to implement something on iOS, but for more detailed knowledge, the developer may be depending on code samples in documentation.

Conversely, a developer who has real expertise in iOS might be winging it in Java-land and relying on your documentation to pull off a basic implementation.

More detail in the documentation is always welcome, but you have to use a progressive-disclosure approach so that expert users aren't bogged down with novice-level detail; at the same time, you have to make this additional detail available for those who need it. Expandable sections, additional pages, or other ways of grouping the more basic detail (if you can provide it) might be a good approach.

There's a reason developer documentation jobs pay more — the job involves a lot more difficulty and challenges, in addition to technical expertise. At the same time, it's just these challenges that make the job more interesting and rewarding.